interview by Lucie Kocourková

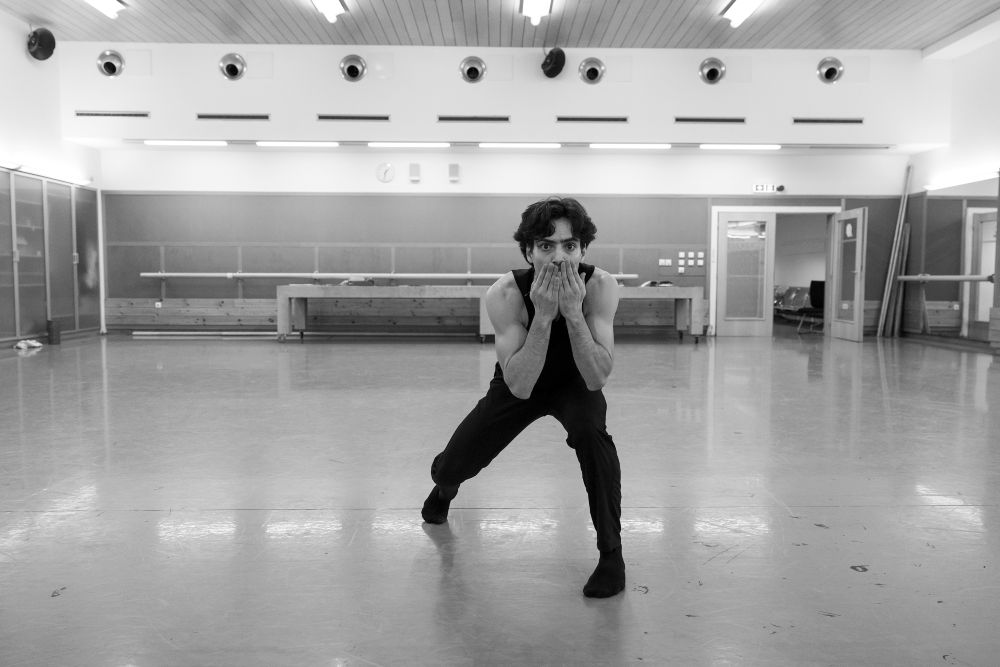

With dancers, we usually talk about their favourite roles and performances, but I am always impressed when they connect their work with some other activity. And when they also have an original take on the world of dance, it’s almost like winning the jackpot. Sergio Méndez Romero, who forms the first couple of the Olomouc ballet with his partner Sawa Shiratsuki, is one such person. He is almost omnipresent on social media, and his activity greatly contributes to raising awareness of ballet. He is also a coach in his field and has just launched a comprehensive programme to help other dancers launch their professional careers. He really has a lot to say, and I am glad that it can be heard from the mouth of a professional dancer. Our talk is therefore quite long and dense, but I also think it is very important.

Worlds of dance art: connected or opposed?

Originally, I wanted to begin with another topic but since we already started talking, let‘s invite the readers right in. I was talking about differences between ballet and contemporary dance as different art forms, where contemporary dance often seeks for attention to social and political issues, and to activate the public, being a space for emancipation and subversion. Yet you talk about ballet as if it possessed equal possibilities. Do you think all types of performing art may serve the same purpose?

I think that art really has duty to motivate and inspire people to strive to be the best person they can be. The problem I see is that on the stage we often reflect the world exactly as it is, depicting the negative phenomena as they are happening, and this undermines the fundamental ability of art to inspire change. How can you inspire someone when you only show them what is wrong? An important part of the work of the artist is missing at this point.

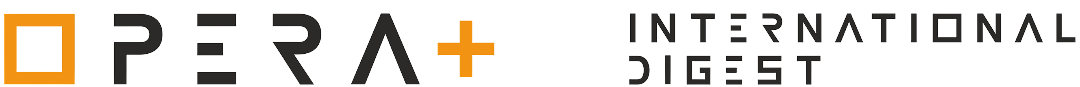

I’m glad when current topics appear on the ballet stage. In Olomouc, for example, the premiere of King´s Court and especially Hidden Secrets. Although I found the second one a bit hopeless, as if it was saying that there’s no point in trying to make a change, since every attempt is doomed to failure. How do you feel about it?

I think the story does not necessarily have to end up good in order for us to understand its positive message. For me, the piece shows certain social change that is currently taking place: we see a lot more people motivating us, we see this change is possible. But at the end of the day, we give up on trying. Somehow, the pressure of the system is pushing us down. I understand how you feel about the piece, but I see it differently. The message for me is that even just trying is worth fighting for. But that’s just my way of living: trying and failing is more important to me, than not trying at all. And I think that the choreographer Garrett Smith had also another message on his mind. Showing us these situations, he is saying: “Listen, this is what is happening. If you don’t take the action now, you will always stay trapped in your dreams, trapped in life with no meaning.”

It was quite clever to leave it open to the people to react in different ways. I like this somewhat activistic concept and in this sense, the piece is contemporary. Though regarding the dance technique, classical and modern languages are the basis.

Yes, Garrett mainly used the classical vocabulary we are used to, but he gave it a different expression. He himself danced with classical ballet companies, but he also worked a lot with Jiří Kylián, so he is one of his creative inspirations.

Jiří Kylián is a great example of how both choreographer and his language change during decades. He started somewhere between neoclassical and modern, but today he dares to deconstruct the movement completely and do crazy things. And you had the opportunity dance in his choreographies in Ostrava, btw.

I danced On an Overgrown Path on Janáček music; I also liked to watch girls rehearsing Fallen Angels. And I danced Wings of Wax, as a spectator I saw Gods and Dogs or Sleepless live on stage. I can see how he changed the way he choreographs, the vocabulary of his movement language while he has remained musical. He’s a master, that’s for sure.

Exactly, here we have such choreographers, who calmly jump from genre to genre and from classical to contemporary dance, living in several dance worlds simultaneously. I also feel comfortable in all of them. But especially here in Czechia, the audiences differ so much, and dances and creators are also somehow divided. Different communities of artists who almost never go to see what’s happening in the other universe. Yet everyone is convinced that they are making art.

Yes, I totally agree, it is sad to see dance world divided. But I understand that everyone tries to preserve what they believe in. Because it takes a lot of courage and power to accept you are just a small part of something bigger. I believe every dance in every art form comes from the same place. If you look at the basic movements and foundation of classical dance technique honestly, you see it is very close to what modern dance and even contemporary dance looks for. Everything is spirals, circles, body expression, we all are telling stories and expressing feelings with our bodies. But we somehow decided to look at what separates us instead of at what connects us. While we should learn how to use aspects of modern and contemporary dance in ballet and contemporary dancers should learn classical ballet. Ballet as art form can actually help with what they do. Because it’s not just about the form, the language, but also the sets or the musicality. How all these elements can be taken in service of contemporary theatre? And how can we turn the topics of today into ballet performances?

Preserving ballet through understanding

Off topic, I’m glad you distinguish between classical dance as a technique and ballet as genre, because you consider the precise meaning of words and terms. There is one topic that concerns me a lot: I am thinking more and more about how ballet is becoming a competition in who can do more pirouettes and faster, who can decorate his jumps au manège the most, who can lift their leg higher. In performances, paradoxically, the demonstration of perfect technique distracts attention from the content. And in my mind, I ask: “Why are you here? And why am I here? Did you come to show me how perfect your technique is, or to tell a story?” I appreciate masterful technique, but if I wanted to see a circus, I’d go to the circus.

This applies to art in general, not just ballet. Art is a reflective mirror. Whatever works on social media, we see it on the stage. When algorithms of social media bring this type of content to more people, we believe that it will work in the theatre as well, to bring more audience and make more money. But why do we have to be this reflective mirror? Why cannot we be the exception that tells we are different, and you can be different as an audience as well? Technique is fundamental, but it can be taken to extremes. We should strive to find a middle ground.

However, we need to reflect more on the value of classical dance, the value of ballet as an art form, and the value of storytelling through this form. I wish we had the guts to stop this madness of just looking for more people to come in the theatre and to focus on high quality and high value of what people come for. This is what in 10- or 20-years period will make ballets undeniable and will keep it flourishing. If we focus on increasing audience numbers and money solely, we will lose those values and one day we will see circus with ballet costumes instead of ballet…

You once wrote that ballet as art form is being destroyed from the inside. There aren’t many artists who think so much about the future of art itself. But here at the theatre, you’ve found like-minded people, as I understand it.

I’m very happy that in Olomouc we are trying to get away from those tendencies. In general, the future of our art depends on how we shape new generations of dancers, and it needs a lot of work. And not just dancers, but also teachers, directors, ballet masters, corepetitors… The whole structure of ballet needs to be changed. And this is a work that cannot be done in one day. Please, don’t take this as a critic of anyone, because it is not a critic, we all are trying to do the best with the knowledge that we have. I’m not better than anyone else. But I can see how different demands are placed on different professions in the ballet world.

For example?

When you want to become member of a company, you have to send your CV with photos and videos, then you have to come to an audition, you must put highest effort into your performance, you have to be noticed and liked by someone and then maybe you get a contract. But when you become ballet teacher, the process to get inside the institution is not as difficult. Sometimes being ballet master with certain experience is enough for you to get a job. I don’t mean to point fingers at anyone. I’m just asking: Why do we measure level of dancers this high, and not the people that teach these dancers to get in that level?

For me, there are a lot of steps that need to be taken into building a strong structure that will make the next generations understand where ballet comes from. There are so many questions. How to get to the next level? How to raise new dancers? How to raise choreographers? How to develop everything? This approach is really missing in ballet world and for me, this is one of the reasons why we are not able to pass everything that it was built to the next generation. People tend to think that new is always better. This is the unfortunate motto guiding ballet world.

During and after rehearsals of Swan Lake, you shared your experience with choreographer Paul Chalmer opening the door to this historical legacy for you, but in a way that was alive and understandable. Is that the thing?

His approach is invaluable. We were not just simply rehearsing Swan Lake. He has such a deep knowledge of dance, he himself danced with best teachers and dancers, and he was talking to us from this perspective. He was not like “This is how I see Swan Lake”, but rather “Swan Lake has been done for hundred and fifty years and this is what these people were thinking at that time. I pass it on you, these years of history to today.” I can see a big difference in that. I’m so happy that we had time to reflect on the history, in order to shape the story for today. And this is what we’re trying to do here in Olomouc. Sometimes it’s visible, sometimes not, which is also part of the process for us to understand how to express ourselves better. But if we deny the new generations from that reflection, how do they understand where things come from and what is this small thing they can add to the history of ballet?

Dancers’ perception. And need for action

What is the message of Swan Lake to you, the Swan Lake you are currently dancing in?

It has many messages. There is, of course, the basic story of the princess that is cursed and becomes a swan and the prince coming to save her. But there are many other ways that we can see this story. For example, Siegfried’s and Odetta’s choreography have many similarities. Maybe everything is happening inside Siegfried’s mind. Maybe he’s fighting with his need of freedom and desire to fly away, while he knows the consequences of leaving everything behind. He’s going to become a king at some point, and he cannot ignore it that easily. The story can be also seen from the perspective of the swan. Why she got cursed, in the first place? Interpretation can differ depending on the ballerina and it can be perceived in many different ways. Not many people think about the character of Rothbart. The story may be about him and the Prince, and the swan is just part of it. I like all those possibilities. Not just the narrative that is on the surface, which can even be perceived as old fashioned for us.

I like getting to know the perceptions of the dancers. Because sometimes talking with the audience, it’s like they only came to see some kind of a fairy tale, which is very simplistic.

I think there are many parallels of the story in today’s society. In the sense that many people feel trapped in some situation and they don’t know how to escape. Maybe they are seeking freedom. And then suddenly someone “happens” in their life that changes everything from how they see life to how they felt love for the first time. This happens every day all around the world. Siegfried in Pauls version understands in the end he has messed up the situation immensely, but for him, dying for his love, dying for these seconds is worth it. This is such a powerful message for people to understand, that when something is real, you know it. And it is worth doing everything for it!

However, how can we encourage viewers not to be superficial and to look for this depth behind the story?

For example, the visual communication is so important. I think we are making a mistake by trying to attract people by the looks instead of teaching them how to dig down. They need something they can relate to, and this will awaken their interest and curiosity. I believe we should not try to make ballet more attractive, but make people feel like they can understand it, that it is not art for the elite. Only few people can do ballet, this is true, but everyone can understand it.

What we can do is meeting audiences more often, showing them what our work really involves, not just the result. Of course, the dancers themselves must understand this too. We have a duty to society. We cannot sit back expecting the audience to understand our work, that’s selfish. We have no right to blame viewers for not understanding us. If we want their money, we have to do something for it. Why don’t we bring the people more in the studio? Why don’t we record our lives and show them reality, not the Netflix series that they see nowadays. Why there is not a series talking about emotions in dance or the duty of dance in society? Because it doesn’t sell. But why we don’t take the risk? Maybe just five people will watch, but that five people will be audience of ballet forever and will pass it on the next generation and that generation to the next generation. But we are short-sighted. We want audiences now; we want money now.

Where does your interest and curiosity come from? How did this happen that you are so interested in the whole process, in the history ballet’s art?

I wasn’t always interested in this, but there were some moments in my career in which I had the feeling that I missed something. That I’m trying to improve myself, I watch the videos of the best dancers in the world and history, I see how they perform, and then when I see myself, I’m like: “It’s not just about the body. It’s not like theirs, but they know something I don’t.” And I have always been very curious and willing to try things. I don’t mind failing. I’m not scared to fail at all. I fell on the floor so many times that I cannot even count it; I made a lot of mistakes, and I still do. But I’ve always had the luxury of the trust from my teachers and from my directors to fail. And I think that this gave me that hunger to know more.

Lifechanging encounters

Is there some special personality that particularly inspired you in this process?

It was so enriching when Fabien Roques came to Olomouc theatre. He started to talk with us about, how for example Nureyev used to work, and all these great artists like Twyla Tharp or Martha Graham… How he went travelling the world, looking for that information and gather it, and how nowadays that’s totally missing… How in the past people were not scared to just go here and there, be curious and ask. It was not just by a click on your phone, you had to take a plane, travel and take classes (perhaps because we have everything at our fingertips, we don’t appreciate the value of information anymore). Thanks to Fabien, everything clicked into place in my head, and I began to understand that it’s not just about the most difficult technique, but that creation starts with an idea, which is then transformed into steps, creating the aesthetics of the work. The process lies in understanding how a line in the text can become a step. An idea becomes movement, and thus aesthetics is born. And that is exactly how a dancer should think when learning a new role. When you do it this way, suddenly your dance looks different. But I see that most people do the opposite, trying to get from aesthetics to the idea.

I have to say I feel extremely lucky that I got to meet some incredible people along the way. When Jiří Kylián’s assistant Stefan Zeromski came to Ostrava to stage Wings of Wax, he said to us: “Listen, you need to create a story here. This piece is based on this painting of Icarus flying to the Sun with wings made of wax that melt, and he falls into the sea. So, everything that you do, has to come with this idea. You need to put it in the steps, you need to think how to show this vision to people.” Same with Paul Chalmer and a handful of other people, trying to share that message, that ballet is not based on aesthetics: aesthetics is a consequence.

When did you meet Paul Chalmer first?

It was 11 years ago already. I danced four of his ballets in total: Cinderella, Three Musketeers, Picture of Dorian Grey and now Swan Lake. I have to say that I learned almost everything about partnering and about looking for sources and contexts from Paul. And Fabian reawakened my love for dance that I lost at some point. I thought it was all about the aesthetic and asked myself, why keep working, when no one cares, no one appreciates. Everyone seems to care only about how tall you are or how high is your leg. And Fabian literally changed my perspective. With Paul, the work was great, yes, but it was always in periods of two months or so, not continuous. Very inspiring, but he couldn’t be there every day to help me make that change. But Fabian was and still is. Both are very important for my life and career and the way I see things. And they have been so generous. When we rehearse, they never hold back, they tell us everything. They stay with us, they teach us not only to dance, but everything around, even how to wear a tiara or do makeup to represent certain character. They teach us how to use space. How the small differences of just positioning of arm can change the meaning of the movement. They are my mentors, and I have no words to express how grateful I am for them.

Which role or production you consider to be the most important to you?

Dorian Gray. The role was created on me and it will remain the role of a lifetime. It’s a pity that it’s already over. This ballet itself is like a painting, a mirror. I believe it should be staged again on a bigger stage with a bigger budget because there were ideas, that could not be fully realised, even though we did our very best. It is such a beautiful story, and the music also is incredible.

What other crucial roles were important to you apart from Dorian?

Solo for Three was a big thing, but not because of the Thalia. When I left Ostrava, it was almost at the end of the Covid pandemic. I didn’t believe I was able to do this production. I got an e-mail from, Michal Štípa and he was like: OK, I want you to dance this role. I watched the recording of the online premiere they did the year before and I thought it was impossible, to synch the French song, to carry such a deep story which is actually not a real narrative at all… There are so many songs, three composers dealing with different topics. All the pictures and situations all together make deeper message, and you need to understand all the texts and their meaning. It was a big challenge because I had just three weeks – after being for two years at home. I remember I was physically exhausted, almost injured by the time of the premiere. But there was only one cast, I had to put all my eggs in one basket. Everyone counted on me, so I had no choice. Solo for Three changed my life in the sense that I believed I could do things I didn’t believe I could do before. And Swan Lake. It means a lot to me, because it’s one of my favourite ballets, but I always thought that it’s not something that I would never experience as a professional because of this ideal image of what a prince should look like. And see, I have already done two versions. Both times it was a very important moment for me.

How did you get all the confidence you have now?

I had quite a lot of struggles before I got to this point. There were many moments during my career when I didn’t believe that I could make it. But somehow, I never gave up. I didn’t try to convince myself that I was good, I just kept going, however bad things were. You know, there is always option to escape. There is always a choice to make. That’s what’s always familiar. But because I never feel scared to fail, I don’t see failure as a bad thing. The only thing that matters is that I will keep going because I love my work. It is not that I am confident because I know I can do it, but because I will keep standing up even if I keep failing. It has been like this my whole life. I know there will always be a new chance, there will always be one more try to do. It’s not about being perfect. At the end of the day, we always have a choice and it’s up to us. Sometimes we encounter situations in which the choice is too painful or “impossible” that we are scared to make it. And that’s totally fine as well. You need to accept this as well.

Couching young dancers

Now you pass the experience to another dancers – which is actually a point I wanted to start with originally. When did you start your online activities?

It was about 4 and 1/2 years ago when two things happened. One colleague of mine died. We were not the best friends, but he really respected me, and he was always somehow here to tell me: “I don’t know what it is, but your dancing is good, even when you fail, it’s good.” After his passing I had the feeling that I cannot keep my work just for myself. What I’m doing needs to be shared, I’m just a channel through which people can get information. And then on Christmas, my brother told me: “Why not just start a YouTube channel? Why not to just talk about what you love and share it with people?” I didn’t even think twice. I was like, yes, why not? I knew I wanted to help other dancers. I didn’t know how to do it or if I would be good at this, but I wanted to try it. I started with sharing my professional life.

So, the coaching part of it came later? How did this aspect come about?

As I learned and experienced my professional life, I started to see certain patterns and understand the reason why some people fail, and others succeed. How they prepare for auditioning, for performances, and what are the differences. And once I found out, I decided to share that knowledge in a structured way, to help someone get from point A to point B. This is where the idea of individual one-on-one coaching came for me. Now a whole programme I called “Ballet Breakthrough Academy”. I’m basically helping dancers creates their dream careers through opening their possibilities, the way they think about themselves and how they position themselves to get opportunities. It’s about what message they send out to the world about themselves, how they can share who they are and who they can be.

Where is the key to success?

It seems it’s very difficult to explain, because everyone, literally everyone in the world is just hiding behind methodology to teach art, while for me for me it is the other way around. They teach you a certain aesthetic and a style to express an idea, instead of telling you: “This is who you are, now let’s put it into ballet.” I’m finding it difficult to express what I’m trying to do, it is a very different approach. But I’m excited and happy that I started this journey.

So, you start from the point of seeing and exploring who the dancer is as personality? What is the typical coaching process?

I work with dancers for a period of six months. This time frame is good to set the pace. Of course, you don’t get to your goal that quickly, but you set a very strong base during this time. First, we define what’s your goal, who you are, what do you really want? To get out of this, there are many questions involved to dig deep into your personality, to help you get to know who you are and what you want to do with that. Then we define what is your artistic value zone, this space between who you are, what the ballet world wants, and how you can position yourself in the middle of that. Once we have that, I will watch you dance, either on video or in person, to see what’s your level. Then we can create a strategy. This is just because it’s so, so important to get to know who you are and what you want to do. So many people go on stage and in the studio and what you can see is like blank paper instead of personality. There is no messaging, no radiation, no idea what they want. Maybe they’re just scared, desperate to do everything correct. For me, breaking that from the first moment changes the whole way you work, learn new technique, go to performances, to auditions, even how you prepare your audition material.

Do you work with people in person, or is your course created using a system of pre-recorded online material? What is the ratio of live and pre-recorded content? Many creators prepare their online courses as a finished product with unlimited access, but with dance, it probably needs different structure.

It is online, but personal, it is not just “follow when you want”, because we are working inside of a time frame. The time management is important. I don’t run a school, the dancers have their work or studies, and I have my work, and in the free time they can use my help. I have some pre-recorded videos, then there are workbooks, and then one-on-one coaching sessions. Lately, one dancer could be here for almost a week personally, so we could speed the process up. There are many options to tailor the programme to suit the participant’s needs. Pre-recorded material is only for us to not waste time on fundamentals. During the coaching sessions, I’m going to tell you how you implement information which I for example talk about in the videos. Because that’s the thing: everyone knows everything, and no one knows how to implement it.

Everyone tells you to improve, but few can explain how, I understand. It’s also about getting general corrections like turn out more and don’t bend your back, but how, right?

It’s just because they also don’t know. They haven’t got that far. And again, this is not against the dance teachers, it’s the system. Because in the schools you follow a methodology, which tells you that in the first year, pupils should be able to do this or that. But this is not teaching ballet and art, this is just throwing information at kids… Why don’t we try to change that, why don’t we put the pressure on teachers? Of course, this has to be taken individually, there are also kids that don’t want to do nothing and then they blame the teacher. But in my opinion, we need to put more pressure on the system. There should be greater supervision of teachers’ work.

How bodies (don’t) communicate

Is there something, mistake or bad habit, that you see often in dancers? And something you recommend paying attention to?

Some of the biggest problems is that almost everyone dances “flat”, technically speaking. People totally forgot how important is to set direction to your dancing, because direction is not only static thing but a very powerful way to express ideas. If you are pointing somewhere but your eyes are totally lost or your body is directed away, the situation loses power, for example. Working with space is so important, because the audience sometimes gets just glimpses of the movement that you create. When your movement is not clear and directed, it gives illusion that the message is not clear even to you. Very important is working with oppositions, it’s important for balance, and because you do not dance only forward, but you are, or you should be, dancing with every part of your body. You need to feel that you are occupying the whole stage. Sometimes when someone has this “big presence”, it is only a consequence of them being able to express everywhere around them, they feel the whole space. There’s also a big problem with placements and turnouts, understanding what placement is and how to use it. Musicality is a crucial thing as well. Those are fundamentals and once you understand them, it changes the whole way you move and express. Before we get into how I can improve my turnout or how I can do a higher arabesque, we need to come back to those basics.

And that means understanding your body and that people need to admit that ballet is also lifetime research of yourself. You actually started your career with an injury. Was this the starting point for discovering your own body and striving to understand it?

I had a serious back injury, almost had to stop dancing because of it. My body wasn’t ready for such a strain. I had way more injuries then, my both shoulders dislocated, I broke my meniscus, I had a finger injury, toes injury, also the neck pain appeared. And it was always because I didn’t know how to do things right. There we get back to the problematic of schools. What is the goal of many of them? Is it to prepare professional dancers, or teach students the syllabus and release them with a diploma? Sometimes also the goal of a ballet company is to sell tickets instead of making art. The same story. When we don’t define the goals, the results are what they are. If the goal of the school is to just make 10 students per year graduate, is it preparing dancers to become professionals? No. A lot of theory, but when you go to the last year of the school and ask the students, what are the steps to develop a role, how do they stand out – no idea. How are they going to keep their body in shape for the whole season? No idea. We tell them they will be prepared for professional work, but they won’t be.

I sometimes feel that young dancers are also unable to communicate their strengths or present their individuality. They are not taught to present themselves, let alone talk about their work. Of course, dancers learn to think with their bodies, but it is not ideal when verbal expression is neglected. Communication skills are important.

This is interesting, since dancers say things like “I dance because with dancing I can express better than words.” But communication has nothing to do with the channel in which you communicate. If you don’t know how to talk, you probably also don’t know how to express with dance, and this is because the same principles apply to both cases. Dance is only a channel; communication is above that. As you say, we need to learn how to communicate and express ideas also with words. It will be then easier to do it with our bodies. It happens again and again with so many dancers that they tell you “This is what I’m expressing”, but then when you see them, it’s like – your body is not telling that. You only think you’re communicating it.

Dancers want to get promoted, get roles. But what kind of message does your body and behaviour radiate? How you behave in the studio every day? This is also communication. Maybe you think you are expressing hunger for new roles: “I am working so hard for it!” But people may perceive you as an arrogant person thinking he’s better than the rest. It’s not important if it is true or not. It’s only about communication and how it’s perceived by the people in front of you. You come from audition thinking “Yes, I did three pirouettes, and my density was good, why didn’t they pick me?”. Maybe your face was saying you were so scared that they didn’t notice you did it right. It doesn’t matter how good you are, if your communication doesn’t say it.

It’s difficult, because students are primarily taught to listen, to behave, to learn technique, to learn variations. But it is often opposite to what they will need in their future life.

Sure. If you don’t teach the students to present themselves, then don’t ask for that later, and vice versa. You know, if we don’t care about the presentation, then it’s fine. But why we teach you something that is not consequent with the future? Again, it’s the whole system in which we try to grow up as artists. It needs to be taught differently. We need to change that culture and mentality. How to do it? I don’t know, honestly, but we can start slowly. We can start just with talking about it, writing and making people aware of these things.

The audience also wields a certain amount of power. If they increasingly go to see dancers rather than titles, theatres will have to ensure that they create an environment where soloists can grow. For change to happen, they must sell names associated with the theatre and the company rather than titles. When we change that, then we push organisations to change their priorities. It will be in their own interest to help principals become dancers that people will love to watch every day. And the audience can play a key role in bringing about the change.

So, once again, we are turning to communicating with people on a more personal level, showing them all aspects of our work and using all the technologies possible.

It is super important to share all this with the audiences because the more they understand the environment and life of the dancers, the more understanding for the art itself comes. The social media presence is very important. Our work needs to be shared. Not just the performance as product, but the whole process behind. And the audience can change the institutions.

How do you feel right now here in your theatre?

I think we are moving in the right direction. Of course, we also have problems, but I feel the atmosphere is nice. I think we’re all in the same boat here, even if we don’t always agree. At the end, we’re pushing to the same goal. I’m happy to be here and I don’t need to hide it. I think we are a great company, and we are doing great work. I think people feel it because our audience keeps coming back for more performances and support what we do.