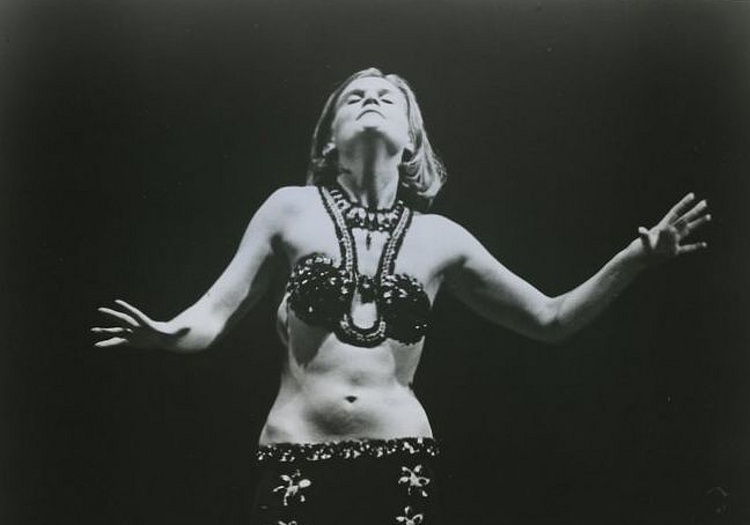

Soprano Anja Silja is a living legend of world opera, often called “the second Callas.” Few singers have sung such a large range of roles. She made her professional debut at 16 as Rosina in Il Barbiere di Siviglia and, at 19, won acclaim at the Wiener Staatsoper as the Queen of the Night. That is what launched her star career, which brought her, at the age of 20, to Bayreuth, where she debuted as Senta. In the following six years, she portrayed all of the important Wagner roles in her Fach and, after the death of her then-partner, Wieland Wagner, she continued with the great dramatic roles, from Turandot to Lady Macbeth. She gained particular attention for her interpretation of the tile roles in the operas of Richard Strauss. She made her Met debut at 1972 as Leonora. At 30, she sang the lead in Janáček’s Věc Makropulos. The critics especially praised her for her great acting and expressive capabilities. She last sang the role of Kostelnička in Jenůfa at the Prague National Theater in 1997. In 2013, she accepted an invitation to a benefit concert hosted by Opera Plus. This year, on April 17th, 2020, she celebrated her 80th birthday. Our Interview Plus series is usually hosted by conductor Jan Bubák in video format. Given the limitations set by the coronavirus epidemic, Jan Bubák had to conduct this interview with Anja Silja over the phone

I must admit it is truly a great pleasure to hear you like this in person. I have a number of your recordings at home and I’ve admired your artistry for some time.

I’m glad. I’m a great fan of all things Czech, as you know, thanks to Janáček, who makes me feel connected to all of you.

Beautifully said. In truth, at least here in the Czech Republic, you are best known as an interpreter of Wagner and also as Kostelnička in Janáček’s Jenůfa, of course, for which you won a Grammy in 2003 (Covent Garden production, conductor Bernard Haitink) yet the range of your work is remarkably broad. Few have accomplished such a breadth of repertoire.

Yes, that’s true. From my beginnings as a coloratura to the dramatic roles and then mezzo-soprano ones – I’ve sung it all.

Do you think something like that could be accomplished by contemporary singers, or was it the result of a certain time and situation?

I think it has something to do with one’s attitude. You can’t be a soprano like aby other and insist: “I’m a soprano. I only sing soprano and don’t want to sing anything else.” I think that soprano parts in particular are limited by age. From a certain age onward, you simply can’t portray certain characters believably, in my opinion. Because acting is very important to me. I sang Salome and all the Wagner roles – all of them are young women, young girls. I couldn’t begin singing Senta at 40 given the libretto. It’ s just not possible. That is why I later decided to sing character roles, Janáček, and others – instead of Elektra, Klytaemnestra, instead of Lulu, Countess Geschwitz. Because that simply pertains to my age.

It’s certainly helps believability… Elsa is a young girl and so is Isolda.

Yes, those Wagner roles, except for Kundra, who is ageless, are all young. Isolda is seventeen, eighteen. You obviously have no chance of seeing that on operatic stages, anymore. I was the only twenty-one-year-old Isolda, worldwide, I think. No one can do that anymore. But that’s how it’s supposed to be. Only then can a person really understand that incredible anger towards Tristan, that terrible anger of Electra towards her mother. The moment I’m no longer able to portray this anger, in other words, the moment I am able to understand why Klytaemnestra did what she did, what her motives were, I can no longer sing Elektra.

For me as a conductor, it’s not just about whether a singer will be able to sing the role physically but, more than anything, whether she can express with her voice the inner tension of the drama. And that ability is often lacking, now a days.

Entirely lacking. Yes, they just kind of sing the notes. I heard a very nice portrait about me in which the host said something to the effect of “Silja is the most modern singer who ever was and, since her, everyone has been back in the middle ages.” And that’s right. They keep relying on beautiful costumes, everything must be beautiful, and sound beautiful, like a century ago.

They say that every – let’s say – dramatic voice must mature gradually but what I see in your bio is that you sang Senta in in Bayreuth at the age of 20. What does a singer need to be weary of so as not to hurt the voice at that age? There’s a big orchestra, a huge stage…

That’s difficult to answer. It depends on your technique. You have to be able to rely on the technique you were taught. But no one really studies it that early. That’s the problem. No one studies singing as early as I did. I started at 6 years old with my grandfather and this basis of my technique always saved me. For all those seventy years of my career I didn’t have a single vocal crisis, the way other singers have.

Does that mean you weren’t scared at all when you first came to Bayreuth?

Exactly. I wasn’t afraid at all. But that’s thanks to youth. When you start so early you aren’t afraid because you don’t know what you should be afraid of. But when you wait to sing certain things until 30 and you’ve had the possibility of hearing hundreds of recordings of a given role by all sorts of famous singers, then of course you start asking yourself whether you’re even good enough. Youth knows no fear, even today. You see that with the Corona virus. Young people are out and about, not afraid of anything. My gift for this career was the fact that my grandfather taught me not to be afraid, as did Wieland Wagner.

Who was your grandfather that taught you to sing?

My grandfather, Anders van Rijn, came from the German-Netherland border, from the region around Düsseldorf towards Rhineland. He was not a professional voice teacher. Singing was his hobby. He was otherwise a painter, a portrait artist. He studied bel canto in Italy with Beniamino Gigli as an amateur, simply out of interest for the human voice, way before I was born. And then when I, as a small child, expressed real interest in singing, he was the one to hammer in vocal technique. And it remained that way – he was really my only teacher.

And which of these gifts is to thank for the fact that you passed through your entire career and so many roles without a single vocal crisis?

It’s thanks to what I had learned. And in my passion for knowing how to do things right. I told myself: “Where in the world should one sing Wagner for the first time? Well, in Bayreuth, of course!” That was my thinking, at nineteen years old. So, I obviously did not feel all that humbled by Bayreuth. I only felt humbled by Wieland Wagner, who was, for me, a great figure in my life, and of course Wagner’s work, though Richard Wagner himself didn’t frighten my at all.

That kind of remove is important, of course. There are, unfortunately, few singers today who wouldn’t approach Wagner with reservations and apprehension.

You’re absolutely right. It’s truly a great error to think Italian opera is easier. I mean it depends on which opera – Rossini, Donizetti, if a person has coloratura, is perhaps easier, but Verdi – Aida, Macbeth – are very difficult to sing. It’s a totally different technique. You can’t think: “First, I’ll sing Verdi or Puccini for a long time and then, when I’m thirty-four, I’ll start with Wagner.” That’s nonsense. For one thing, this has nothing to do with age, but something else. Many singers are scared and their voices aren’t penetrating enough. A voice has to carry well otherwise you won’t get anywhere.

Does it make you happy, that you still have the tytle of a Wagnerian singer?

Yes, I’m still labeled that way. Somehow, that label still clings to me, though, since Wieland’s death in 1966, which is a good number of years ago, I never sang Wagner again, except for Ortrud, thirty years later with Robert Wilson, and that was only because I never learned that role with Wieland. Otherwise, I never sang Wagner again. Yet I’ll never shed this image of the Wagnerian singer.

When we imagine a Wagnerian voice, it’s usually a heavy, strong voice that can withstand a lot. History tells us, however, that the first interpreters of Wagner were bel canto singers. Do you think the idea of the Wagnerian voice changed over time and, if so, how?

Yes, that’s a problem of conductors because they conduct everything so loudly. Tristan for example is chamber music. There are only five singers on stage, so you can’t hammer into the music so much. But many conductors do. Even other Wagnerian works aren’t conceived to be played so loud the singers can barely sing over it. This is a misunderstanding between the orchestra and the singers, to think that these Wagner voices need to be covered with so much sound and that that is why Wagner requires these huge voices. This is a vice of today. Yes, you do need a truly penetrating voice, the kind that Brigit Nilsson had and the kind I had, but it doesn’t have to be so extremely big and broad. Broad, that is how these Wagner voices are described today. But that isn’t by far what Wagner imagined his singers to be, otherwise so many of his characters wouldn’t be young girls.

I think that everything is getting louder, because of these tendencies, even singing itself. If we listen to old recordings, though recording technology was certainly limited back then, we can understand the words much better. People sang differently.

Yes, and that is how they taught singing back then. Wieland always emphasized this: “I don’t understand what you’re singing over there. You have to pronounce the consonants, not mutter vowels to yourself.” People used to put much more emphasis on this. Today, conductors don’t arrive until the last rehearsals, because they’re performing elsewhere before that, and, what’s more, pronunciation isn’t that important to them, anyway. And that’s really too bad. The only conductor I know who still cares about words is Kirill Petrenko. He truly emphasized language, or at least he did fifteen years ago. I hope he still does.

And do you think that the idea of the Wagnerian voice changed in part as a result of this shift? That that’s why so many of the voices associated with Wagner today are broad, with big vibratos?

It’s become a kind of slogan: “That Wagner voice.” But this is a bit of a mistake, I think. Wolfgang Windgassen, for example, sang Mozart until the very end of his career, first Tamino, of course, and then Monostatos. So, light repertoire. Also Florestan in Fidelio, of course. Today, however, there are singers who truly sing only Wagner and after five, six, seven, eight years, they can barely sing anything. That’s crazy because then they just scream. It’s happening often, now, even with big names, who are singing in a thousand different places at once. They shout everything with enormous force and that’s truly a tragedy.

Can we come back to your partner, Wieland Wagner? Like you said, you sang almost no Wagner roles after his death.

No. Only the things I had already signed for. But no more Wagner after that. I dedicated myself to other roles and then I had my great Janáček period.

Why is that? Was it out of respect towards

Wieland Wagner?

Yes, that was an emotional

decision. To this day, I can’t hear that music without constantly seeing him

before me and getting emotional. It’s too stressful.

How do you remember Wieland Wagner as a person and a director?

Those last five years I experienced with him we were together constantly. After all, in those six years during which we collaborated, we created thirty-six productions together…

That’s unimaginable! Six productions a year…that seems almost impossible.

Crazy, isn’t it? It’s true. One after the other. I sang everything Wieland directed. Everything.

Was he benevolent or strict as a director? How did he work?

He was capable of being very unpleasant when he saw that someone wasn’t taking it seriously or wasn’t well-prepared. Otherwise, he was very helpful, patient, and precise in his direction and very modern in how he interpreted things.

His work basically set the foundation for today’s regietheater.

Absolutely. He put great emphasis on how believable something was, which wasn’t always so easy given that Wagner singers are always on average a bit older. That is why he took such an interest in me. I was exactly the age Richard Wagner had in mind. Unfortunately, he was never able to find a young Tristan, one younger than Wolfgang Windgassen or Hans Beirer. The closest he came was Jess Thomas but finding a truly young Tristan who would have fit my age was impossible and will remain so.

Did he usually have a strong, unmovable idea of the direction he wanted or did he accept suggestions made by singers?

This was the incredible thing about him. He worked completely differently with each singer. Whether he was working with Leonie Rysanek, Brigit Nilsson, Wolfgang Windgassen, Jess Thomas, James King or me, his process was always different, in harmony with the singer he was working with. So he never said: “I imagined it this way and that’s how you have to do it.” Never. He always worked individually with the particular singer he had before him.

I’d like to talk a little more about your great dramatic gifts. It’s rare to find a singer who would be capable of connecting singing and acting as well as you.

I’d formulate that differently. I connect shaping the character with singing, not the other way around. That’s the big difference. That’s why I always said, when talking about the roles I started doing later, that what I was always most interested in, when it comes to opera and music, were the characters, not so much the music itself. First and foremost, I must express the character, that is what tells me how I should interpret the music. That is the thing that truly fascinates me.

Take The Makropulos Affair: I sang it for the first time in 1970, in German, in Stuttgart with Václav Neumann. I liked him very much as a conductor. I was very young back then, only thirty. I didn’t understand the character – at thirty, you have no understanding of a role like that. I sang it like she was a great diva and uncompromisingly wanted that elixir back, the end. When you sing her at fifty, sixty, however, with some life experience behind you, when you, too, have also lost a lot of people, like I lost Wieland Wagner, and André Cluytens and others, you see her life philosophy and understand why this woman is so aggressive and why, despite everything, she still wants to live – because that’s all she knows how to do. That is an insight that one doesn’t arrive at until later in life and this supports the interpretation and understanding of what the music even means.

I’ve heard that in opera, there are certain limitations with acting, because you’re singing and acting at the same time.

There aren’t. A lot of singers insist: “I can’t sing when I’m kneeling. I can’t sing lying down.” Simply put, that’s a question of technique. If you know exactly how to position the voice you can keep singing, even if you’re standing on your head. That’s how I did it with Wieland. He said: “You can do it, you can do anything” and I would say “You need strength for that, I can’t do it.” “Yes you can,” he would say. And I did.

I’d actually like to ask again about the beginning of your career. At sixteen, you sang Rosina, Micaëla, and Zerbinetta. How did your colleagues accept you? I can’t even imagine.

Well, they weren’t too happy, that’s true. They would say “What is this child doing here?” But the intendant believed in me and said: “She can do it.” I didn’t much care what these colleagues wanted from me. Not at all. Some of them did finally accept me, others complained about me from the beginning, but that’s just how it was. When I left for Stuttgart two years later, I was still only eighteen, but was a bit more established, and then at twenty in Frankfurt there was no problem at all – everyone got used to the fact that there was this young singer around. But when I was just starting out in Braunschweig it wasn’t easy. I now have some understanding for my colleagues. The roles I was taking were ones these seasoned singers could sing, if it weren’t for me. I understand they weren’t thrilled about that.

Which conductor was important to you when you started working on Czech repertoire?

The one who got me closer to Czech music and the Czech language was Jiří Bělohlávek. He was extremely important to me and I really admired him and loved him greatly. He was a fantastic conductor. He was important when it comes to Janáček. At Glyndebourne, where we first met working on Jenůfa, he really helped me with my interpretation and the language. So my pronunciation kept getting better and better. It was very difficult in the beginning, but he put incredible emphasis on the language – going back to what you said before about conductors not putting enough emphasis on it. He, for one, found it incredibly important.

I studies with him briefly at the Academy of Music and I remember his pronunciation sounded very pronounced even to a native speaker.

Really? As an artist he was incredible at working with language. He kept stopping and correcting and this was very difficult. You were constantly afraid that you had pronounced something wrong, again. But I learned a lot from him.

Sometimes people say our language lacks long, arched phrases and that we tend towards jagged rhythms. It’s not exactly a bel canto language.

No, it really isn’t a language for bel canto but it doesn’t have to be. Czech operas aren’t written as bel canto. This is especially pronounced in Janáček. He basically used the language of everyday life. When I arrived in your country, I recognized every third word people were saying. Of course, I didn’t understand the words, as I had simply memorized the text, but I realized that those words I was singing are in constant, everyday use. I was fascinated by the fact that Janáček composed to folk speech. Like I said, I always felt wonderful in your country – at first when I did Salome at the National Theater (editor’s note: under the baton of Jaroslav Krombholc). That was in 1966 and, thirty years later, Bělohlávek told me his father would go listen to me repeatedly at the theater and talk about me all the time. That makes one happy – not to be forgotten.

Let’s return to Kostelnička from Janáček’s Jenůfa for a moment. That is a very specific role. In 2003, you won a Grammy Award for it. Did you always sing the version of the role which included the aria in the first act?

Yes, usually with the aria.

And did you know that Janáček cut this aria during rehearsals for the opera’s premiere in 1904?

Well, that’s strange because it’s important to explain what happened to this character and why she’s so weary of Laca and Štěva.

That’s true but I think Janáček, in the end, must have decided that it isn’t necessary for everything to be served so easily to the listener. Perhaps he wanted the audience to pick up on things gradually.

Maybe it had something to do with the times. I myself consider the aria important. I’ve sung Jenůfa without the aria as well – they cut it in Covent Garden, for example. But, later, Bernard Haitink and Bělohlávek performed it with the aria. I consider the aria very important because it makes the character a lot clearer and it becomes clear to the listener why she reacts so aggressively towards men.

And it also explains the family relationships.

Yes, exactly. Those aren’t really explained in any other place in the libretto. You wouldn’t understand what’s happening in the entire second and third act if you don’t understand the family history. It must have been a bit of a phenomenon of Janáček’s time that he didn’t want the aria but I don’t think we should go back to that.

I also think this is kind of an endless discussion between singers and conductors. The interpreter of Kostelnička often wants to keep the aria so that she can have her moment right from the start. The aria is printed in the orchestral score, with a note that says it was cut by the composer. The editors left it in print, anyway.

Well, yes, that remains a bit of a question – what if the original had been modified by the composer? There are instances of this in Wagner, too. For example, he rewrote the ballad in the Der fliegende Holländer a step lower for Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient. This lower version was performed from then on and it wasn’t until my debut in Bayreuth at twenty years old, that I sang the higher version thanks to Wolfgang Sawallisch. Only, I think, Christine Lindberg used this version after me. Otherwise no one. It’s probably simply too high for most sopranos.

And also all of the cuts in Tristan and Isolde were not just anyone’s invention – Wagner himself came up with them. For example the big duet “Tag und Nacht” in the second act was often cut. And there are other passages which one will be hard-pressed to ever hear – but if it’s because of the composer’s actual wishes or if it was cut out of consideration for a particular singer or situation – we can’t, in my opinion, know that for sure. I consider Kostelnička’s aria very important for her character and Jiří Bělohlávek also left the aria in, and that is how they continued to do it at the Metropolitan opera. Bělohlávek definitely believed in that aria.

You have been active in the world of opera for over 60 years. Much has changed in that time…

Oh, yes. It used to be such an enormous pleasure, especially after World War II. It was, of course, a new beginning for all opera singers, back then, as it likely will be after this pandemic. It was a time of great artistic challenges – productions had a very high quality, and it wasn’t necessary to constantly say “she’s famous, he’s not famous.” There was a kind of unity back then. Everything has become very commercial. If someone who doesn’t have a name isn’t singing, people don’t even want to go to the theater. I consider this terrible.

Do you feel the future is much more difficult for today’s young singers than it was for you when you were starting out?

I do. Because people stopped going to the theater for the singers and now directors are putting together these hallucinatory productions which have nothing to do with the work at hand. Singers absolutely have no way of developing in such an environment – they stand there and sing, then they get crammed into car or something, on stage, or they sit at a bar, or the action is moved into a hospital room – always according to the ideas the director has at the moment. It’s hard to create characters that way. This is a big problem for young singers who, usually, sing very well, technically speaking, but that becomes secondary.

Are you afraid that directors might eventually destroy opera with these innovations?

Yes, I would say that if they continue in this manner, then they definitely will, because I know a lot of people that don’t go to the opera anymore, simply because they have no interest in seeing such things. They want to see at least a hint of what the opera is actually about, be it Salome or the Tales of Hoffmann. They don’t want to see it transferred to a prison, or for Marzelline to shoot Pizarro, like in the London production of Fidelio. That’s crazy! Why? Out of love for Leonore? That love doesn’t exist. It’s just Marzelline’s enthusiasm for Fidelio, whom she understandably considers to be a man. That’s laughable. And directors come up with these ideas just to draw attention to themselves. And the singers? Who was singing, actually, if it wasn’t someone with a name like Jonas Kaufmann or Bryn Terfel? No one speaks or writes about the others. This irritates the audience, too, and that is why they go to the opera so reluctantly, because they know that they won’t see what the music is describing. I hope these crazy ideas will end, one day. They’re not interesting, anymore, and we need to kind of return to the core of what the world is made of. Here I have to mention the pandemic again. The air we breathe has become a lot cleaner than it was three months ago. We’ve come back to nature a bit. Everything has to end, one day, and that reveals new and interesting paths.

I completely agree with you.

I wanted to tell you that I love your accent in German, maestro. It is so familiar to me and reminds me of my dear Czech friends.

Thank you and I wish you a happy birthday!

Send my greetings to your beautiful country in these strange times!

Goodbye and thank you for a wonderful interview!

Special thanks to tenor Štefan Margita for helping arrange this interview.