interview by Tomáš Pilát

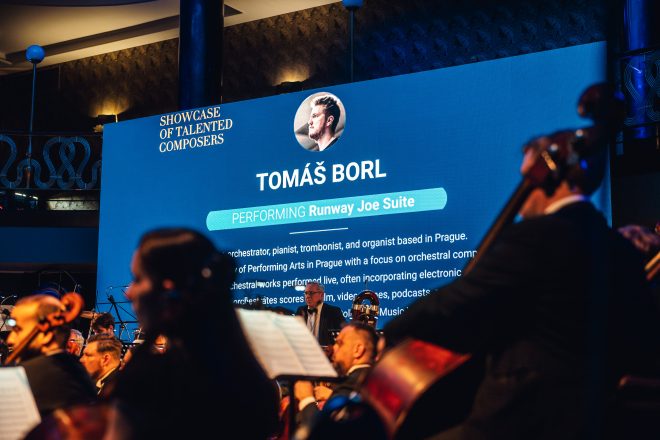

A Czech rising star is setting out on an international journey. Tomáš Borl – a composer, arranger, orchestrator, and instrumentalist, as well as a graduate of Prague’s Academy of Performing Arts (HAMU) – has become the first Czech to receive an exclusive scholarship to the renowned Berklee College of Music — at its only European campus, located in Valencia, Spain. Beginning this September, he will enroll in the master’s program in film, television, and video game scoring, whose alumni include composers working with Netflix, Disney, and HBO. Before his departure, it is the right time to sk what awaits him, how he rose from his roots in the town of Louny to international recognition, and perhaps even how he composes in water.

You have received a scholarship to one of the world’s most prestigious music schools. What does this mean to you personally?

For me, it’s a huge challenge. Although I already have experience composing music for various media – from film and video games to investigative podcasts – I still see myself primarily as a concert composer. What I truly enjoy is receiving a dedicated timespan from a philharmonic, an ensemble, or another commissioner who entrusts me with it, and then shaping it musically to the fullest – considering, for example, the flow of form or the evolving relationships of musical ideas over time. Writing for the screen is, in that sense, a different discipline, even though certain skills – such as orchestration – can be transferred from concert work. In fact, during the admissions process some of those “concert” skills were praised – so I suppose I am not entirely wrong in saying this.

Studying in a program grounded in practical experience is an invaluable next step in my artistic path, one that also brings with it a sense of responsibility. It is also a kind of bridge between Berklee and Prague — specifically through the Composers Summit Prague festival and Soundsgate. And it is only thanks to the newly created imaginary bridge between these institutions that Im able to pursue these studies, with the support of The Kellner Family Foundation and the Czech Copyright Association (OSA). My aim is to represent my supporters, and the city of Prague itself, in the best possible light at Berklee. I am spending this summer preparing carefully for that mission.

How is the academic year at Berklee organized? Can you adjust your schedule to your own needs – for example, to spend less time on what you already know and focus on what you really need?

The master’s program lasts one year and is divided into three trimesters. The first introduces students to a broad range of methods and technologies. In the second, they work on mastering the acquired skills, and in the third, they must demonstrate in practice that they can apply everything effectively. This final trimester includes recording a graduation project with an orchestra — composing music for a specific film — as well as writing the thesis. The program as a whole is strongly practice-oriented: graduates leave equipped with solid knowledge, professional experience, and a portfolio recorded by some of Europe’s top orchestras.

Berklee provides a comprehensive education in film scoring, covering the entire creative chain: composition, preparation of parts and technical documents, recording sessions, and post-production, including editing, mixing, and mastering. Students learn how to guide a project from its earliest consultations all the way to the final cut. They also gain thorough training in the software widely used today, since not everything is recorded with a live orchestra — sometimes the result must be achieved using sound libraries and digital production. A film or game composer must be prepared to work outside their comfort zone, and learning to navigate those challenges is part of the education.

Your studies include composing and recording in legendary studios like Abbey Road. How significant is it for you to be working in such a place where, for example, the Beatles made their legendary albums?

It will be an extraordinary experience. I should clarify, though, that master’s projects are not recorded exclusively at Abbey Road, but also at the famous AIR Studios, depending on availability – in either case, the music is performed by a professional London studio orchestra. Since it is a very costly process, each student is allocated a limited amount of recording time, and it is entirely up to them how they use it. Some take the baton themselves, while others prefer to work with a music director. I’m leaning towards conducting the orchestra myself, though it will be a great challenge – and I’ll have to learn a lot more so as not to bring shame – especially in such legendary halls.

Your musical range is very broad – you compose, arrange, and orchestrate music from classical to film, game, and jazz. Do you anticipate that your work will shift more toward film and game scoring after completing Berklee’s Master’s program?

I’d like to diversify my portfolio as much as possible. I can’t say exactly which direction it will take, but I definitely want to devote more time to film and game music. Of course, much will depend on networking and participation in creative teams. I think concert music and film music don’t have to be mutually exclusive; in fact, they can complement each other very well.

You studied trombone and piano at the Teplice Conservatory. What led you to choose the trombone, a relatively uncommon solo instrument?

I started out on the trumpet, but due to my physical build I switched to the trombone. For example, I have wider lips, which suited this instrument better. I try to maintain my practice as an orchestral player too — it’s the best way to understand what is comfortable for musicians to play and what isn’t. Recently, quite a few trombone pieces have been composed, though some composers focus mainly on flashy effects, others on themes that aren’t very memorable, and some compositions sound like forgotten military marches. Meanwhile, I know plenty of skilled players who would prefer performing more lyrical, melodic passages than just show off tricks.

The trombone seems to be a personal favorite. How often do you play it nowadays, either as a soloist or as a composer?

The trombone is a fantastic instrument because of its versatility – you can play lyrical melodies or build strong harmonic foundations with several players. Its dynamic range is impressive; it can sound angelically soft or intensely powerful, making it ideal for orchestral music. You do have to be careful, though, because in forte, the brass section can easily overshadow the rest of the orchestra. I try to use trombones effectively — not too often, but in the right moments. In general, I enjoy writing for brass. I don’t want to overuse them, but sometimes my hand slips, and I write them even where they might not strictly be needed. I just like them.

At the same time, I don’t focus solely on the trombone — I continue performing on piano and organ. I’m extremely grateful to have had the chance to perform as a soloist on all these instruments with various philharmonic orchestras. I consider it a tremendous education and my own kind of “Olympic triathlon.”

Where does film music stand within Czech music education? Can aspiring composers get a foundation at music schools or conservatories and then build on it at the university level?

While film music is indeed part of the curriculum at Czech higher education institutions, the Berklee program distinguishes itself by offering a fully integrated pathway: from initial sketches, through score preparation, to professional orchestral recording and the complete post-production process. Each phase must be independently managed by the student, ensuring both technical competence and artistic persuasiveness.

In the Czech Republic, such a comprehensive system doesn’t yet exist. The focus here tends to be on independent projects, which usually require a very different kind of music — if music is given space at all. If you want to learn about orchestration and real collaboration with musicians, you typically have to go abroad.

At the conservatory or basic music school level, it depends more on individual interest and on communities of enthusiasts forming around shared passions. Very often, those networks last a lifetime. Writing for film is intellectually and technically demanding, so it’s not really a discipline for complete beginners. But for anyone motivated, a good place to start is through collaboration with students of film, animation, or multimedia — and that, in fact, happens quite often.

Remind us where audiences may have come across your music – in film, TV, streaming platforms, or even video games – and what exciting projects await you next?

Not long ago, I worked on a podcast broadcast by RTÉ Studio One in Ireland. Out of that soundtrack, my colleague Martin Klusák and I shaped a concert suite – Martin wrote the majority of the music, but we complemented one another beautifully, and I look back on the project with great fondness. The podcast went on to win the Prix Europa 2024 – something like the “European Podcast Oscars.” Thanks to this success, the soundtrack was released, and the suite is also set to be performed by the Irish National Radio Orchestra. I’ve also worked as a ghostwriter for a gaming studio – something that wasn’t intended to be ghostwriting at first but ended up that way. It was a fascinating experience and really showed me how much success in this medium depends on human communication – on being able to follow the lead composer’s vision closely and becoming a vital part of a larger whole.

As for film scoring, I collaborated with Nukleon Frame, composing music for both the bachelor’s and master’s graduation films of director Vojtěch Konečný. His bachelor film was even nominated for the Czech Lion Award in the student category. Although we did not win, it was a significant honor and a wonderful experience. Some of my upcoming projects are covered by NDAs, so I can’t say more for now. At the moment, a lot of my energy is going into preparing for my studies at Berklee.

And how about your concert works?

Here I am free to speak, and fortunately, there is plenty to talk about. I maintain an ongoing collaboration with trombonist Ko-Ichiro Yamamoto, former member of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic, as well as with the Austrian duo of trombonist Peter Steiner and organist Constanze Hochwartner. Ko-Ichiro regularly performs my Trombone Concerto around the world, from the United States to Japan. Looking ahead, there are major plans for two solo organ works that Constanze is preparing to present on her upcoming international tour.

My duet for two trombones recently had its U.S. premiere, initiated by John Sebastian Vera of the Pittsburgh Opera, who has also performed my music in Texas. For a while, I was getting requests for scores from trombone professors across U.S. universities – and more recently, from students in Japan.

I must also mention my dear fellow instrumentalists from the academy, who premiered several of my works in the Czech Republic before they began to travel internationally. These collaborations were always rewarding experiences that, I dare say, enriched all of us involved. Thanks to recordings from those concerts at home, I was able to reach out to, and sometimes be approached by, foreign soloists. What pleases me most is that the feedback tends to converge on the same points: performers find my music surprisingly natural to play, lyrical, memorable in places, emotionally engaging, and often sparking unexpected musical associations.

When you compose, do you think about how your music will be understood by general audiences – listeners who experience it emotionally rather than intellectually?

Honestly, it’s impossible to satisfy everyone, and thinking about that too much would just distract me from composing. There are so many genres and subgenres, and each has its own audience. What I do rely on is my “inner judge” – I try to be as objective as possible while writing, and that in itself can be surprisingly demanding. During my time at the Sibelius Academy in Finland, Professor Matthew Whittall actually wanted to teach me how to reach this “objective state,” and we were both amused to discover during my very first lesson that we already spoke the same language in that regard.

What I find harder to understand is the common urge to link a concert piece to some grand narrative, or to highlight a particular compositional method at all costs. More than once I’ve witnessed a composer becoming so fascinated with a single idea that the music itself slipped away – it lost its persuasiveness or simply fell apart. My own approach is almost the opposite. I’m fascinated by sound itself, by the qualities of music without extra-musical associations. And when I have to provide program notes, I’ll admit that I usually search for those “extra-musical meanings” only afterward, once the piece is finished.

When did you receive your first offer to compose film music?

It was for a student project – a short film of about ten minutes. Just before the premiere, however, the director decided to re-edit the entire film, which meant that the original score no longer fit. On the eve of the premiere, I had to compose an entirely new soundtrack to match the new structure. It was a fascinating experience – very stressful, but ultimately an instructive one.

Film music can be created in different ways – based on the final cut, a rough cut, or even just the script. Sometimes a composer writes from nothing more than a verbal outline of a scene. Which method works best for you?

I would say I’m more of a systematic type. I like to analyze the film from various angles, both on a macro and micro level. I ask myself: what’s really important here, what stirs emotions, what acts as a dramatic trigger, and is there something running quietly in the background that the music could foreshadow? Every project has its own demands. Film music today is incredibly precise – it’s all about timing and a deep grasp of dramatic flow. With video games it’s a different challenge: the score needs to shift and respond to the player’s actions, which calls for even more careful planning on the composer’s part.

Work on film or video game music is largely collaborative. The score must respond dramatically to the unfolding events, which are defined by the screenwriter and director, or in games by the designer. In contrast, when you write a symphony or a chamber piece, you compose on your own. Does this mean that in film and game scoring you have to adapt significantly to the demands of other creators and engage in extensive communication?

Definitely. A film composer has to stay in close contact with other members of the team – the director, editor, sound engineer. The more questions you ask and the more you understand the overall vision, the fewer revisions are needed and the more efficiently you can work. You also need to be able to respond quickly, sometimes even scrap your original musical idea and start fresh. To me, film scoring is something for true enthusiasts – “heart-driven” people. The conditions can be tough: limited budgets, limited time, and high expectations. That’s why teamwork matters so much, along with good organization, the ability to handle pressure, and an openness to collaboration.

In video games, all of this becomes even more intense. I wouldn’t say it is harder than film scoring, but it is a different type of challenge. The music has to adapt and change in real time based on the player’s decisions, which requires special compositional strategies, technical know-how, and close teamwork with game designers.

Sometimes in film a musician acts both as composer and sound designer. That seems like the ideal situation, also for communication with the director…

It’s certainly a great advantage if a composer has some reach into other fields – to understand sound design, or even to create some of the sounds themselves. This comes in handy especially with independent projects, which often move in a more abstract space and give the composer more freedom to connect the score with the sound world. If the composer is able to merge the musical, noise, and sound layers into a single whole, the result can be a truly powerful experience. However, it is by no means a necessity – even though, for example, at the Sibelius Academy we were encouraged during our game music lessons to develop precisely this integrated approach.

How common is it, here and abroad, for a composer to be asked to rewrite or re-record the music – for instance, because of mistakes or changes in direction?

From my experience at masterclasses like Composers Summit Prague or the Hollywood Music Workshop in Baden – where Conrad Pope also taught – I can say it’s fairly common. Major changes often occur at the very last moment, and composers must be ready to react quickly. Sometimes, across several thousand pages of score, only three errors are found, which in the given time and scope is practically a miracle. But more often, things have to be rewritten or adjusted simply because of new decisions from the director or the production team.

Some composers invent new musical instruments to enhance the atmosphere of a film. Have you ever created or built such an instrument yourself?

I haven’t invented a new acoustic instrument yet. Rather, I’ve experimented with combining acoustic instruments and electronics, which produced relatively unusual, but hopefully interesting timbres. And it’s true that sometimes exactly what you describe happens: a new instrument or sound effect is invented specifically for a film scene, a motif, or even a character. Film scoring leaves a lot of room for experimentation and originality, qualities that are certainly valued today. But in general, I think every composer aims to create music with a unique color, even without inventing new instruments. And in concert music, I’d say that aim is even more pronounced.

In your opinion, can film music serve as a bridge for listeners to other genres – for instance, to contemporary classical music?

Absolutely. Film music operates at the intersection of many genres. At times it incorporates elements of contemporary classical music; at others, pop, jazz, or ambient. It can be a subtle, even educational way of introducing an audience to a new musical language – without them necessarily realizing it. Always gently, accessibly, and only if it serves the scene and the story.

A great example is John Williams’s score for the third Harry Potter film. With Alfonso Cuarón stepping in as director and aiming for a darker feel, he turned to contemporary classical music for inspiration and asked Williams for something along those lines. The result was a masterful mix: in addition to textures inspired by contemporary idioms and, of course, several neo-romantic themes, Williams employed atonal jazz, minimalist layers, and passages evoking Renaissance techniques and instrumentation.

And returning briefly to video game music, which you have also worked on: do you see this as a field with a future?

Definitely. And here in the Czech Republic, we have much to be proud of. I’d like to mention my colleague Jan Valta, who composed the score for both editions of the internationally acclaimed game Kingdom Come. His music is personal and grand, an orchestral soundtrack of immense scale, sometimes reminding me of John Williams or the great Czech composers at their very best.

Game music is a very specific discipline. The composer must anticipate how the music will be implemented in the game, when and how different layers will trigger, and what the transitions and dynamics should be. It’s not a matter of simply sitting down and writing. Planning several steps ahead is essential. Close communication with game designers is required. There is a bit more freedom in terms of timing – you don’t need to match every cut perfectly (except for cutscenes) – but there are other unique constraints, sometimes thematic. Retro games, for example, have a sound that demands a specific approach. Often, the final version of the game is only revealed very late, sometimes long after the music has already been composed. For the composer, this presents a challenge but also a wide canvas for creativity. I truly believe there is a tremendous future in game music – it’s an extremely dynamic environment, technologically, artistically, and personally.

Do you have any hobbies outside of music?

Yes. In creative work, it’s perhaps more important than anywhere else to take a break, switch gears, or completely disconnect for a while. I’m a fan of motorsport, especially Formula 1, and I also like to go swimming whenever I can. I’m not a professional swimmer, but I try to cultivate discipline even outside music – sometimes I manage as many as a hundred pool lengths.

Everything is connected, though: several times while swimming, musical ideas or even entire phrases have come to me. I’ve found that moving in the pool stimulates my thinking, and twice I’ve effectively “finished” a composition in my head while swimming. Later, I wrote everything down on my phone in the locker room. Over the long term, I aim to maintain a strong and detailed internal sense of music, so I’m not dependent on an instrument or a computer. I rely primarily on my imagination, and nowadays I don’t think I could work any other way – it saves me several compositional steps.